Context:

Indian economy has an income problem, not a growth problem. Incomes are not growing sufficiently or sustainably for very large numbers of people. Even though overall GDP growth is good, there is increasing pressure for reservations of jobs for all “economically weaker” sections regardless of caste or religion.

Growth and employment:

Economists on both sides, for the government and those against it, are debating whether the economy is creating enough jobs and are questioning the veracity of the government’s data. Those against the government also want to show that the problem of growth with insufficient jobs has been created by the policies of the present government and not the previous one.

Jobs that are not ‘good’:

- The overall problem of incomes in India, according to economists, is that insufficient numbers have moved out of agriculture into manufacturing. This has been the historical pattern for sustainable growth in all countries, including the U.S. a hundred years ago, and China more recently.

- India’s policymakers thought they had found a shortcut in the 1990s, directly from agriculture to services, with the boost in the growth of exportable Information Technology services.

- But there is very little room in high end services to absorb the large numbers of young Indians in need of jobs. Moreover, these jobs require levels of education that people in rural areas do not have. Therefore, when they move out of agriculture, they need work that fits their present abilities, and puts them onto a ladder that they can climb. They need jobs where they can learn higher skills and earn more.

- Labour intensive manufacturing, services, and construction provide them the first step. The millions of Indians who have moved out of agriculture in the last three decades moved into such jobs.

- The problem is that the jobs they have, irrespective of the sector, are not “good” jobs: they do not pay enough, they are temporary or on short contracts, and they do not provide social security or assistance to develop further skills.

- Even in large, modern, manufacturing enterprises, workers are employed through contractors to provide employers with “flexibility” to reduce costs. Contract workers are paid much less than regular workers. They have insecure employment and are not assisted to develop higher skills.

The world at a turning point:

- New ideas of economics are required to create a more environmentally sustainable and socially harmonious future. New concepts of work are required; also new designs of enterprises in which the work is done; as well as new evaluations of the social and economic relationships between participants in these enterprises. The drive for green, organic, and “local” to reduce carbon emissions and improve care of the environment will make small enterprises beautiful again.

- “Economies of scope” will determine the viability of enterprises rather than “economies of scale”. Denser, local, economic webs will develop, rather than long, global supply chains through which specialised products made on scale in different parts of the world are connecting producers with consumers in other distant parts.

The economic value in caregiving:

- Attention will shift towards creating genuine “social” enterprises, rather than enterprises for creating economic efficiencies and surpluses which corporate enterprises are designed for.

- Those who provide care, and their work of caregiving, must be valued more than economists value them today. In the present paradigm of economic growth, caregivers, traditionally women, are plucked out of families — which are a natural social enterprise — to work in factories, offices, and retail, in enterprises designed to produce monetary economic value.

- When economists measure women’s participation in the labour force, they value only what women do in formal enterprises for money. They seem to assign no value to the “informal” work they do outside their homes to earn money, whether as domestic caregivers in others’ homes or on family farms.

- The prevalent paradigm of economic theory is distorting social organisations, which families are, to suit the requirements of corporations, which are formal economic organisations. Thus, the money measured economy (GDP) grows, while the care that humans can and should give each other reduces.

Measurements of economic growth and employment:

- It must not be mired any longer in 20th century concepts of economic growth. They must be reformed to reflect forms of work and enterprises we want more of in the future.

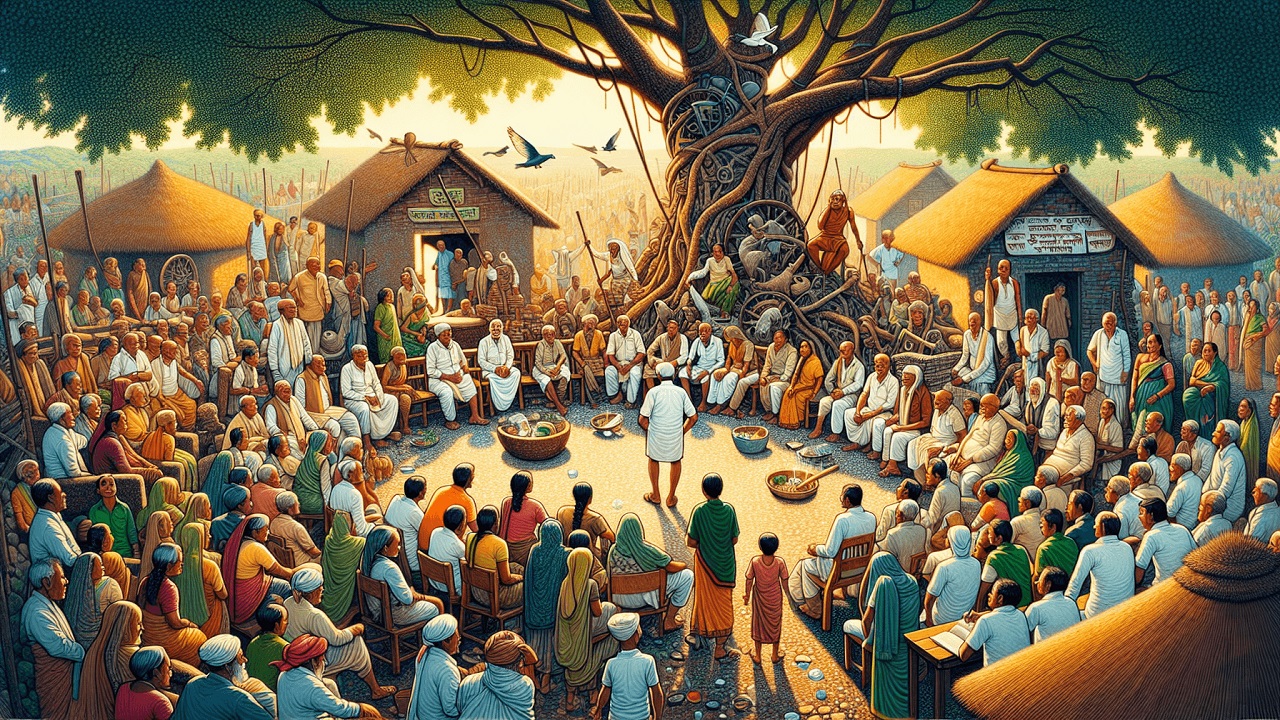

- For this paradigm shift, the process of policymaking must begin with listening to those who have not been given much value in the present economic paradigm: to workers, smallholding farmers, small entrepreneurs, and women. Presently, their views are overruled by those who have power in the present paradigm: experts in economics, large financial institutions, and large business corporations.

Conclusion:

The lesson for policymakers is this: “Don’t count on historical statistics to guide good policy for the future: listen to the people and what matters to them.”

.jpg)

.jpg)

Comments (0)